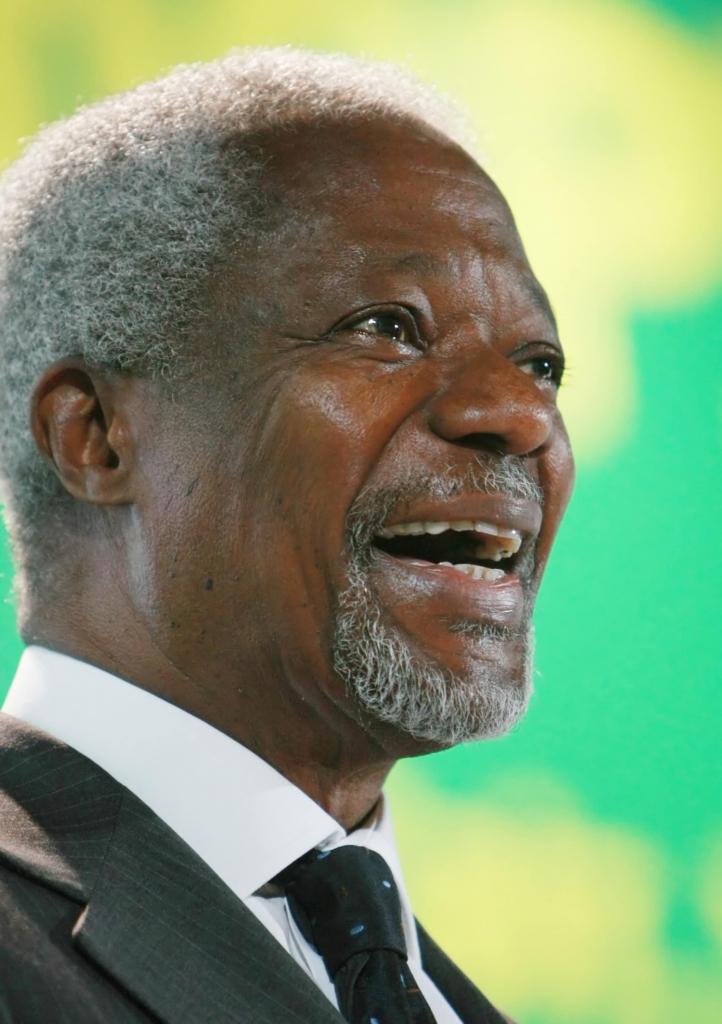

He was not my boss, not my mentor nor someone I worked with. He is, however, someone whom I regard as one of the greatest leaders of our time. The three times I met the man are still as vivid in my mind as they could be. I would have loved to be on his team and in some way, I felt that I was.

In the wake of the death of Kofi Annan there have been countless tributes from his close friends as well as from political leaders around the world. It is a celebration of Annan’s statesmanship, his many accomplishments, but also accolades for his persona, his elegant diplomacy and his profound commitment to world peace.

Kofi Annan rose from within the United Nations system and ended up spending his entire career trying hard to reform the UN. Some of the admiring political leaders now praising his legacy could certainly have done much more to support him during his 10-year-tenure as the UN’s seventh Secretary General. He was, after all, the person they in 1996 put in charge of the aging and very often questioned organization.

Before I became a bona fide enrolled student of international relations, I came across Kofi Annan in Zagreb in 1994, during the war in former Yugoslavia. He was then Under-Secretary-General and head of The Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO). I was a sergeant in the Swedish contingent of UNPROFOR’s headquarters. I had a keen interest in peace and security, human rights and democracy and volunteered for every opportunity to learn more.

My unit worked security at the UN headquarters downtown Zagreb. We managed access to the HQ and security at press conferences. We were also the UNPROFOR honor guard during high-level visits or ceremonies for fallen UN peacekeepers. At night, we checked that offices were locked and confiscated any classified document that senior staff such as Yasushi Akashi (Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the former Yugoslavia), Force Commanders Cots or later De La Presle had left on their desks. We had instruction to take classified material to our “safe” and leave notes on the desk for the person responsible to collect. Even a quick peek at these documents (including cables between Boutros-Gali’s office, Annan, Stoltenberg and his predecessor Akashi, and others) clearly revealed the Undersecretary’s key role and tireless efforts to manage the ongoing conflict.

During one of Kofi Annan’s first visits to Zagreb as head of peacekeeping in the spring of 1994, we performed the honor guard. As the color sergeant for the day, I was on point with the UN banner. Given that Yasushi Akashi was Japanese, we often had very eager Japanese journalists present and this occasion was no exception. As Kofi Annan arrived to inspect us together with the Force Commander and Akashi, we came to attention and I held the flag parallel to the ground proudly displaying the UN flag. The Japanese photographer was on my left behind the ropes but in trying to get his perfect shot of Annan & Co. saluting the UN banner, he stepped forward and onto the lower end of the flag. I was not amused and responded by whacking him in the chest with the pole. Annan must have caught this in the corner of his eye, because he grinned and said “Thank you” to me before whispering something to the Force Commander, who laughed.

At the press conference later, I had volunteered for security detail and was at the back of the room with a couple of my men. It was then that I started to realize the greatness of Kofi Annan. In his deep steady voice, with its distinctive British-African accent, he took on tough questions without hesitation and gave compelling answers that had not previously heard coming from that podium. Needless to say, I was impressed. When he passed me on his way out, he looked up at me, smiled and said: “Keep up the good work”. I responded “You too, Sir”.

Two years later, I learned from the news that Kofi Annan of Ghana had become the new Secretary General. He replaced Boutros-Ghali who had been blocked by the US for a second term. Working in UN system was something I had already hoped to do and with Annan at the helm, I was even more inspired and applied for an internship at the UN secretariat. My three tours as a peacekeeper and particularly my security experience from Zagreb landed me in the UN Office for Security Coordination (UNSECOORD, today UNDSS). My supervisor of this rather small office was the iron lady of UN security, Mrs. Diana Russler. I mentioned to her my admiration of Annan and the photo incident in Zagreb. She laughed and said it sounded like him and went on to tell me Annan had been in charge of UN Security on his way up in the UN system. As I recall, she knew him quite well and had the deepest respect for him, much for the same reasons that I admired him.

As an unpaid intern 20 years ago, most of my lunches were sandwiches and instead of the cafeteria, I spent many of my breaks in the stands in the Security Council, listening to among others Kofi Annan. I attended every session at Dag Hammarskjöld’s library where he would speak and understood both how influential he was to the organization and how limited his relative powers vis-à-vis the UN Security Council was. He balanced his duty extremely well. He was a true internationalist and went on to launch the Global Compact in the hope that more countries would reap the benefits of international cooperation and globalization. He always stressed that the world is interdependent and that no one country can succeed by itself. Viewing the world as such also meant that the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 was a big a disappointment and personal failure for him.

The summer batch of interns to which I belonged came from very different backgrounds and was a diverse crowd. At the time, every cohort of interns got a photo-op with the Secretary General in the Indonesian lounge at the UN secretariat. Waiting for Kofi Annan, I remember how the photographer put a chair in the middle of room to gauge his equipment. My intern friends from Africa immediately clung to the chair: Annan was a rock star. More than that, one intern from Ghana told me that for them he was evidence of African greatness. Kofi Annan entered the room and immediately changed the atmosphere. He spoke at length and talked about giving the UN charter, however imperfect, a human face and true meaning. He challenged us to become international civil servants and ambassadors for the organization.

Years later, I worked with humanitarian assistance with UNICEF in New York. With two small children, we spent countless hours in Central Park, often with my youngest on my shoulders. It was a warm September weekend, only a few months before Kofi Annan left office. We were walking not far from the boathouse when I spotted Nane Annan followed by a bodyguard, a Danish guy I knew from Zagreb. Right behind them was Kofi Annan.

I stopped on the narrow path and as they approached, Kofi stopped and said, “You have a beautiful son”. This was my chance: this was an opportunity to close the loop of a decade of thought and thousands of pages of reading and writing on peacekeeping, Rwanda, Balkans, Iraq, globalization, human nature. Take your pick.

What came out in the moment was just: “Thank you” and as Kofi Annan continued his stroll with his wife, my wife caught up with me and asked, “What did you say?”. I told her I was at a loss for words - which I have never been before or since.

I never saw him again and now he is gone. He was not my boss, not my mentor or someone I worked closely with. He was someone I did not have a conversation with in the park. I still regard him as one of the greatest leaders of our time, a time when real leaders are desperately needed and in short supply.